After years of low crop prices and rising costs, America’s small farmers are facing a crisis brought on by higher interest rates, Trump’s trade war and dramatically reduced demand from China.

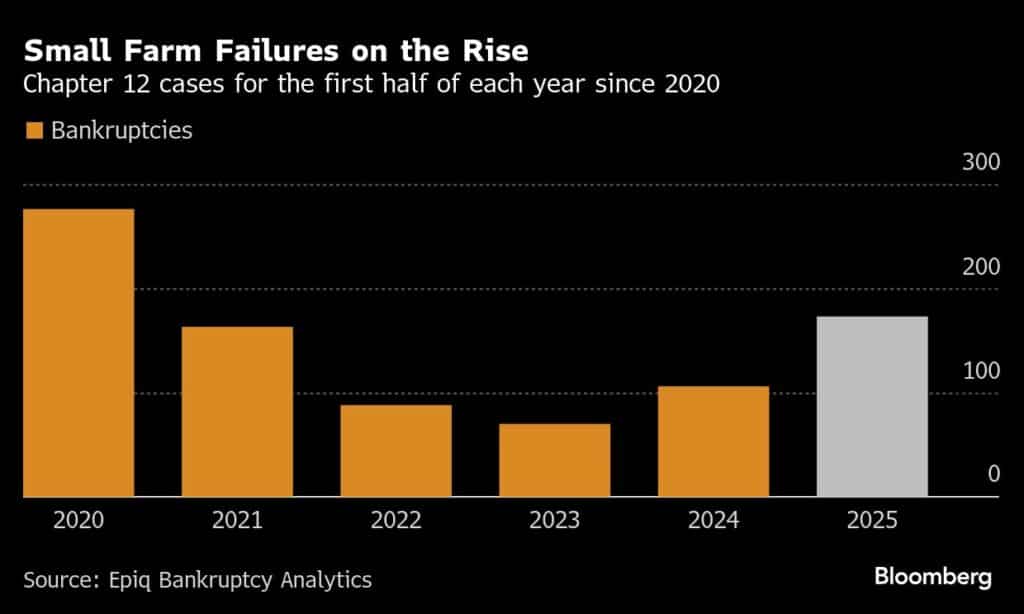

In the first half of the year, small-business bankruptcies filed by farmers and fisherman hit the highest number since 2020, which was the tail end of a similar cycle of low-prices. Farm debt is expected to hit $561.8 billion in this year, a record high, according to the US Department of Agriculture.

“We’ve had three years of tough sledding here where breakevens are at or below cost,” said Brett Bruggeman, the chief operating officer at Land O’Lakes Inc., one of the biggest farmer-owned cooperatives in the US.

Soybean, corn and pork producers have been among the hardest hit farmers in recent years as China began buying more from competitors in Brazil and other parts of Latin America. Before President Donald Trump’s first term in office in 2017, US farmers dominated the Chinese import market, said Joseph A. Peiffer, with the Iowa-based law firm Ag & Business Legal Strategies. Today Brazil occupies that position, he said.

“Once you lose a customer it’s awful hard to get them back,” he said. Firms that specialize in restructuring farm debt have seen an increase in business, lawyers said.

Land O’Lakes said its members are seeing dwindling cash reserves and growing concerns about the 2026 crop year. More new growers have been applying to a Land O’Lakes program that helps finance crop inputs like seeds and nutrients.

And in order to manage costs, executives at local farm retailers are getting involved in purchasing decisions usually handled by procurement managers, said Leah Anderson, the president of the company’s crop inputs division.

“There’s just more stress, and the level of rigor and discipline they’re having to use at the local level just to make sure that they stay in position is certainly higher than I’ve seen in the past,” Anderson said.

Although the USDA forecasts net farm income to rise in 2025, that improvement is largely driven by government assistance. Returns from growing crops like corn and soy continue to drop. The last two years, overall farm incomes declined.

“Now we are seeing farmers run out of liquid cash after trying to ‘just make it to next year’ several years in a row,” said Ryan Loy, an agricultural economist and assistant professor at the University of Arkansas.

Lenders have pulled back from the farm business as the industry has struggled. Farmers borrow heavily at the start of a growing season and pay off those debts when they sell. To protect themselves, lenders are tightening collateral terms, bankruptcy lawyer David Mills said. For example, more lenders are making a claim on crop insurance payments, which farmers receive after being hit by bad weather or a drop in prices, Mills said.

And as local banks have pulled back on farm loans, specialty firms have stepped in with higher interest rates and more onerous terms.

Arkansas has been the hardest hit state in the recent uptick in small-farm bankruptcies. About 25% of all farm bankruptcies this year were filed there, according to Loy.

In Wisconsin, dairy farmers have had trouble hiring workers because of Trump’s push to round up undocumented workers, said Mark Harring, a court-approved trustee who oversees small-farm bankruptcy cases.

Even filing bankruptcy can be difficult for small farmers. Those with less than $12.5 million in debt are able to use special rules that protect family homes by forcing lenders to adjust the mortgage. That benefit is not typically available in a traditional Chapter 11 case, lawyers said.

But to qualify for a Chapter 12 farm bankruptcy, the owner often must sell equipment or other assets and then use the cash to slash debt below the $12.5 million limit.

Farm woes have also started to trickle down to the local businesses that rely on farmers.

Instead of buying new tractors, that can cost $250,000, many farmers are hunting for used equipment, said Mike Gurkins, with Country Boys Auction and Reality in North Carolina. “They don’t have the extra cash,” he said.

— By Steven Church and Ilena Peng (Bloomberg)